The most poisonous plant genus of Europe consists of at least a hundred different species and has an array of legends and folklore attributed to it. Not by chance it is called a ‘queen of poisons’ and ‘plant arsenic’ – in reference to arsenic, the ‘king of poisons’.

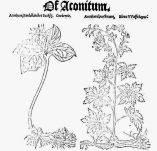

A distinction sometimes found, concerns the names monkshood and wolfsbane. Some consider the white or yellow-flowered species Aconitum lycoctonum the true wolfsbane, whereas the blue flowering Monkshood (Aconitum napellus) is probably the better known of the two species. The latter is found in medieval monastery gardens. The two species contain different poisons, however similar – and both lethal – in effect.

A distinction sometimes found, concerns the names monkshood and wolfsbane. Some consider the white or yellow-flowered species Aconitum lycoctonum the true wolfsbane, whereas the blue flowering Monkshood (Aconitum napellus) is probably the better known of the two species. The latter is found in medieval monastery gardens. The two species contain different poisons, however similar – and both lethal – in effect.

Name origins and legends: The Greek word akónitos is composed of ak = pointed and kônos = cone, an akon being a dart or javelin, which is perhaps a reference to the plant’s use as arrow poison. Theophrastus suggests, the name is derived from the town of Aconæ (thought to be located near Karadeniz Ereğli in Turkey). It may also have been named after mount Akonitos in Pontus (Asia Minor)

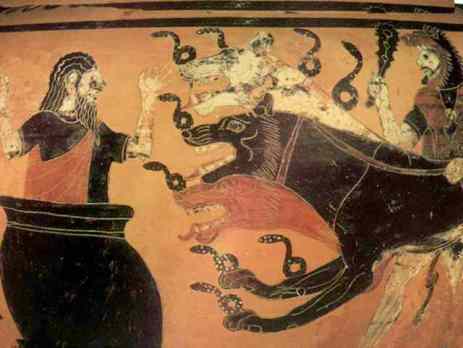

According to legend, it was near this mountain in Pontus, where the plant grew from the spittle of Cerberus, the three-headed hound of Hades, when folk hero Heracles drew up the beast from its infernal abode. Homer (800 bc) gives the first account of this myth in the Illiad. Eight centuries later Ovid embellishes the story in Metamorphoses VII, where Scythian sorceress Medea attempts to poison Theseus with aconite. Aconite features also in Metamorphoses VI: Athena sprinkles Arachne with aconite, upon which she is transformed into a spider (VI, 129ff.).

According to Ovid, aconite was also called ‘flintwort’ or ‘stoneherb’ by farmers of the region, because the plant was found growing on barren rocks. Pliny the Elder agrees with Ovid, in that he states the name aconite was derived from aeonæ = rocks.

Besides, the legend surrounding Cerberus dates back to the time of Hesiod (800-700 bc), who describes the creature as a fifty-headed do and being the offspring of Typhon and Echidna. Typhon is refered to as birther of storm winds and father of all monsters and was viewed as the largest and most deadly of all creatures, whereas Echidna was envisioned as a monstrous viper and mother of all monsters. Their ‘poisonous’ blood flows in the veins of Cerberus and inside the vessels of the plant that rose from his saliva.

Aconite is also named hecateis, after the goddess Hecate. Hecate is an ancient Greek goddess of witchcraft, associated with crossroads, gateways, knowledge of herbs and poisonous plants, the souls of the dead/ necromancy and shape-shifting. In this latter aspect she is called upon as Lycania. Aconite is also thought to have been used by Thessalonian witches in hallucinogenic flying ointments.

The Berserkers, an infamous Germanic tribe, reportedly consumed Aconite in order to transform into ‘werewolves’. Aconite is said to cause a sensation on the skin of wearing a fur-coat or feathers and may induce hallucinations of transforming into different kinds of animals. Indo-European culture holds the name Luppewurz, from old German luppi = deathly juice/poison/spell, and similar to Latin lupus = wolf. The Greek byname lycoctonum means wolf-killer, possibly referring to the plant’s use in poisoned wolf baits. Hence the plant is also known as Wolfsbane in modern English language.

Dioscurides distinguishes two species: Akoniton lycoctonum is mentioned as an anodyne in eye medications, and was used to “kill panthers, wolves, and other wild beasts” (see also Virgil). the second species is Aconitum napellus, which is used to “kill wolves”. (De Materia MedicaIV. 77, IV. 78) Dioscurides also states the name napellus comes from Latin napus = a small turnip.

Pliny the Elder refers to the herb as ‘plant arsenic‘, and dedicates chapter 2 of The Natural History to the “most prompt of all poisons”, which he claims, was also an antidote to scorpion poison. In the same context Pliny mentions the white hellebore (Veratrum album) as an antagonist to aconite. He goes on to describe the use of aconite and hellebore as pardalianches = pard-strangle.

Aconite in poison murder: The most poisonous herb of Europe, aconite has a long history in poison murder. Pliny reports of Calpurnius Bestia, who killed his wives in sleep by touching their genitalia with his finger, which were smeared with aconite root extracts. According to Pliny aconite was hence also known as thelyphonon = ‘female-bane’ or ‘woman killer’. (Aconite brought in contact with the mucuouse menbranes of female genitalia would indeed cause instant death!) Pliny suggest yet another name for aconite, scorpio, was based on the curved shape of the root, which was thought to resemble a scorpion’s tail. Another example for poisoning with aconite features the, perhaps, most famous suicide of all times: Cleopatra, pressed for time, may have killed herself with the help of a poisonous cocktail containing aconite, poison hemlock and opium poppy rather than the bite of a cobra.

References in Germanic folklore: Aconite was sacred to Thor, the Norse god of thunderstorms and lightning. In German this connection is reflected in various folk names given to the plant, such as Sturmhut and Thor’s hat. Other popular German names are Eisenhut = helmet, and Mönchshut = monk’s hood. But there is also an erotic side the aconite, as is suggested by names such as Venuskutschen and Venuswagen = ‘wagon of Venus’. Here we have a contrast to the male and martial names and attributes, suggesting female and aphrodisiac qualities. However, the names are often simply based on various interpretations of the shape of the flowers. Related to the plant’s poisonous effects are names such as Würgling, indicating death through asphyxiation, and Ziegentod, referring to the deaths of goats that accidentally ate the plant.

Aconite use as arrow poison: Aconite has been used as an arrow poison in hunting and warfare. Arrow heads were dressed with aconite as well as the shafts, so that an enemy, who drew the arrow from the body of a wounded comrade, would be poisoned too. In India, aconite was mixed with other poisons and applied to arrowheads, so that the targets would rave mad and poison more people by biting them. Aconite’s use as an early biological war weapon extends also to poisoning the enemy’s water and food resources, e.g. the Romans used it as such. Roman Emperor Claudius died of aconite poisoning in year 54.

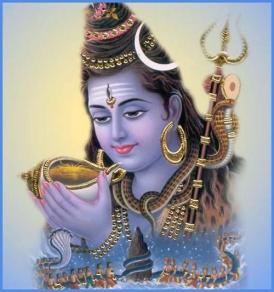

Sacred to Shiva: In India, aconite is sacred to Shiva, who is, amongst others, also worshiped as a god of poisons. According to legend, the essence of all poisons (Hala hala), spread from the whirling motion of the ocean of milk, Samudramathana, when it produced the holy cow. The gods were frightened and ran to mount Kailash, where Shiva sat meditating, and asked him for help. Shiva took the poison in his hands and drank it. His wife Parvati feared for her husband and choked his throat so that the poison eventually would get stuck and upon which his throat turned blue. Because of this Shiva is also called Nilakantha = blue throat. Through his deed Shiva saved all beings from becoming poisoned. Only a tiny bit of the poison had dripped from his hand which until today flows in the veins of the blue aconite and other poisonous plants. Another version of the story tells of Shiva having turned blue from consuming all the poisons in the world. In his likeness, Aghoris consume poisonous plants, such as Aconitum ferox, Cannabis indica, Datura metel, Papaver somniferum and other poisons, e.g. cobra venom, quicksilver, arsenic, to experience the divine consciousness of Shiva. Advanced practitioners consume a smoking blend of Cannabis indica and Aconitum ferox, which is called vatsanabha or bish root. The Saradatilaka tantra describes Shiva Nilakantha:

“He shines like a myriad of rising suns, he wears a shining crescent moon in his long entangled hair. His four arms are adorned with snakes. He has five heads, each with three eyes, he wears a tiger skin and is armed with a trishula.”

Aconite in Christian iconography: Aconite appears in Christian iconography as a symbol of death and it is the symbol for toxicity in European nature. It was a classic in Christian medieval monastery gardens. There exists a fictional account of its use by Christian monks in Gustav Meyrink’s novel The Cardinal Napellus. The story is about a brotherhood named the ‘blue brothers’, who believed that cardinal Napellus, the founder of their order, had transformed into the very first aconite plant and all further aconite plants had derived from him. Aconitum napellus features on the order’s coat of arms and the monastery garden is a huge aconite field, planted by neophytes after admission into the order. In the story these neophytes sprinkle the plants with the blood that flows from their scourging wounds. “The symbolism of this ritual of blood baptism lies within the planting of the human soul inside the garden of Eden and fertilizing the plant’s growth with the blood of men’s desires.” The members of the order are described, using the plant for inducing hallucinations or gaining higher consciousness:

“When the flowers vanished, we would collect the poisonous seeds, which resemble small human hearts and according to the secret doctrine of the order depict the seed of faith, of which is written that it lends the power to move mountains, and they would eat from it. As the dreadful poison transforms the heart and brings men to the liminal point betwixt death and life, so the essence of faith was meant to transform our blood – to become a miraculous force within the hours of deathly agony and ecstasy.” – Meyrink 1984

Sources and further reading:

Aconite Drug Information + Aconite in Plants of Greek Myth + Aconite in The Natural History of Pliny the Elder + Aconite in Ovid’s Metamorphoses + Aconite in Homer’s Iliad + Dioscorides, De Materia Medica IV. 77, IV. 78 + Hesiod, Theogony + Hercules and the Hydra + Panacea: Potion Ingredients +